算数の評価に関する視点の理解にMAXADAを利用 – 教育研究事例

MAXQDA Research Blog 翻訳版

Guest post by Natalie Nóbrega Santos, Vera Monteiro & Lourdes Mata – Centro de Investigação em Educação, ISPA – Instituto Universitário (Monday, May 11, 2020)

評価とは何でしょうか?「(評価により)つけられた成績が良ければ、良い仕事に就き、お金を得て、良い人生を送れるようになる」(ある3年生の発言)。生徒が評価をどのように認識しているかは非常に重要です。なぜなら、生徒が持つ考えが、彼らどような姿勢で学習取り組むかを導き出し決定するためです (Brown & Harris, 2012; Brown & Hirschfeld, 2007)。また、教師が評価についてどのように考えているかも同じく重要です。なぜなら、教師が教室で評価をどのように実施するかの指針となるためです(Barnes, Fives, & Dacey, 2017; Brown, 2008; Brown, Kennedy, Fok, Chan, & Yu, 2009; Opre, 2015; Vandeyar & Killen, 2007)。

背景: 小学校の教師や生徒は算数の評価についてどのように考えているのだろうか

教師と生徒がそれぞれ独自に持っている評価についての考えは、すべてが共通しているわけではありません。これらの考え方は、教師や生徒の行動(例:指導や学習戦略)や学習の情緒的要素(例:動機づけ)に影響を与える可能性があります。本研究は、教師と生徒の評価に対する概念と教師の評価実践が、生徒の成果にどのように関係しているかを探ることを目的とした研究プロジェクトの一環として行われました。特に今回の研究では、ポルトガルの小学校の教師と生徒が算数の評価についてどのように認識しているのか、またどのような点が共通しているのかを明らかにしようとしました。調査の過程でMAXQDA のツールを使用しています。

研究データ

本研究には、小学校4校から 5 名の教師と 3 年生 82 名(クラスA、B、C、D、E)が参加しました。5人の教師との個別インタビューと、生徒とのフォーカスグループディスカッション(クラスD:2グループ、クラスA・B:3グループ、クラスC・E:4グループ)によってデータを収集しました。

教師との会話では評価に関する5つのトピックを取り上げました:

- 評価の定義

- 対象

- 目的

- 実践

- 評価基準

生徒には3つのトピックを用意:

- 定義

- 目的

- 実践

MAXQDAによるデータ分析

コーディングプロセス

MAXQDA を用いて内容分析を行いました。インタビューとフォーカスグループの逐語録を、算数の評価に関する参加者のさまざまな経験を記述した断片にコード化しました。演繹的アプローチと帰納的アプローチの両方を用いています。ブラウン(Brown, 2008)が以前示したカテゴリーから始め、これらのカテゴリーを参加者の現実を代表するものとして再定義する循環的なプロセスを適用しました(Miles, Huberman, & Saldaña 2014)。

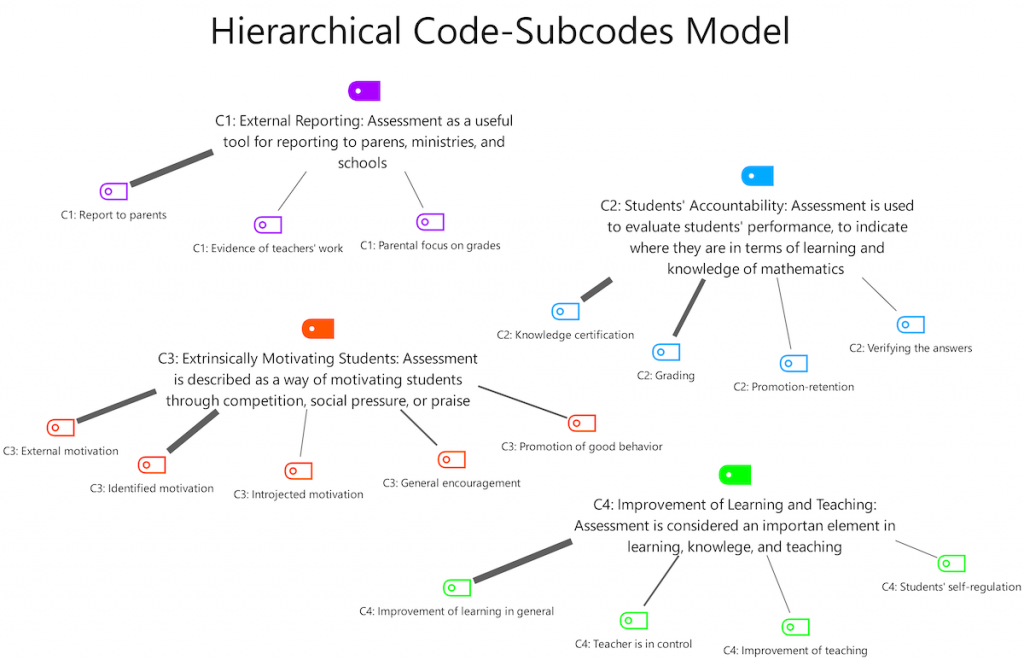

また、分析の質を高めるためにサブカテゴリー(サブコード)を定義しています。特定した質の異なる評価概念は以下の4つです。

- 外部(親、官庁、学校)への報告

- 生徒の成果(知識や学習がどの段階にあるか)に関する説明責任

- 生徒の対外的な動機付け(競争、社会的な圧力、賞など)

- 学習と教育の改善

図1は、MAXQDAの[MAXMaps]機能を用いて作成した最終的な階層構造のコード・サブコード体系で示すコンセプトマップです。線の太さは,参加者の発言の中でコードが割り当てられた頻度を示しています。

結果の可視化

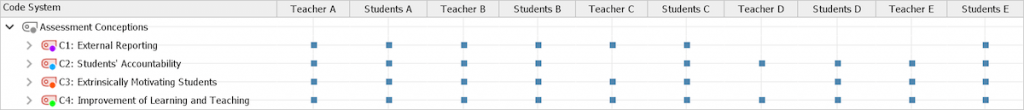

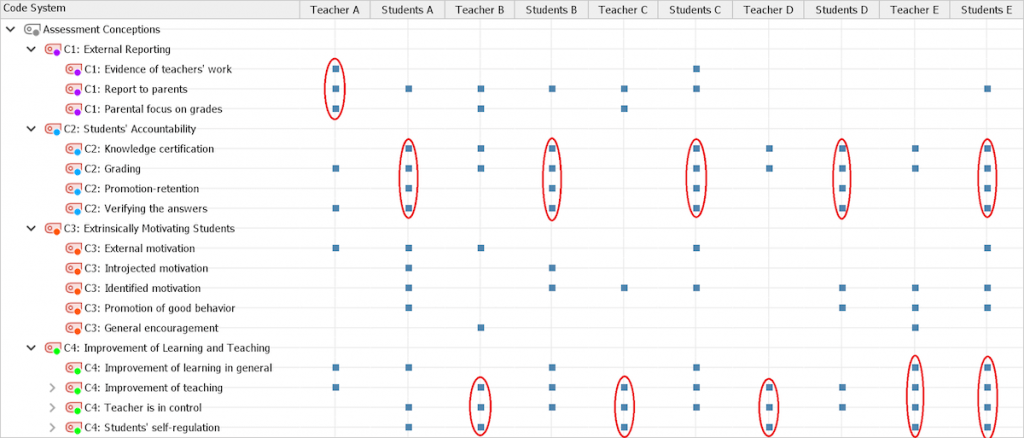

MAXQDA の[コードマトリックス・ブラウザ](図 2)では、教師と生徒が 4 つのカテゴリすべてを反映した評価の概念を持っていることが見て取れますが、これは Barnes ら (2017) によって示唆された評価の信念の多次元的な性質を裏付けています。

教師と生徒は評価について相反する信念を持っていると思われますが、この時点では参加者間の明確な違いは見られません。

分析を深める

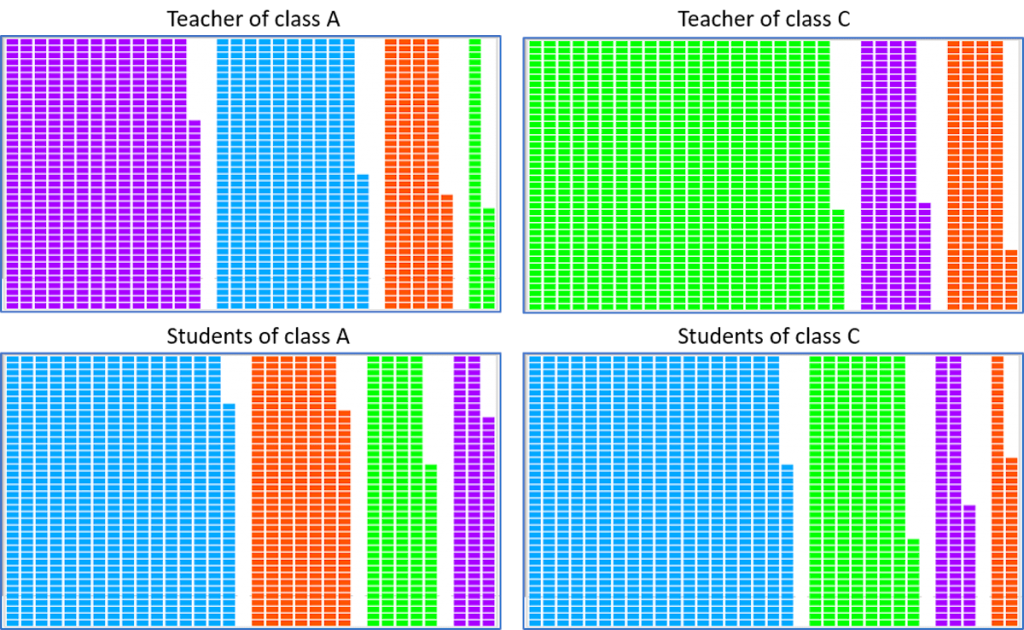

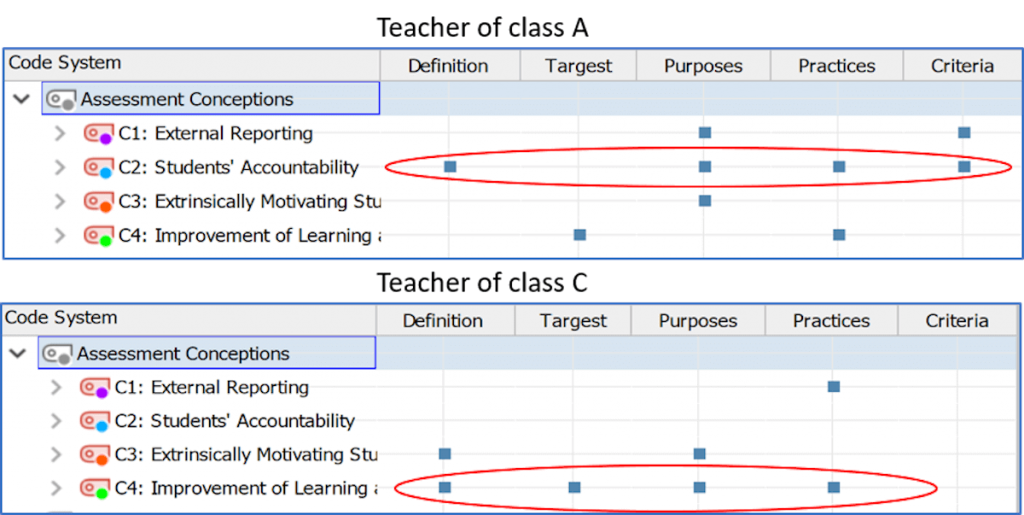

参加者の評価概念をより直接的かつ正確に分析するために、MAXQDA のいくつかの機能を使用して、各教師とその生徒の間で最も支配的なカテゴリーを特定しました。MAXQDAの[文書概観表示]を使い、参加者が最も頻繁に言及したカテゴリを可視化しました。これは参加者が最も重要だと感じたカテゴリを反映していると考えられます(図3)。

発言内容が豊かであること、さまざまな側面(サブコード)について言及していることは、そのカテゴリをいかに深く理解しているかを反映しています。そこで[コードマトリックス・ブラウザ]を使い、各参加者がより多くのサブコードにコードされているカテゴリを特定しました。

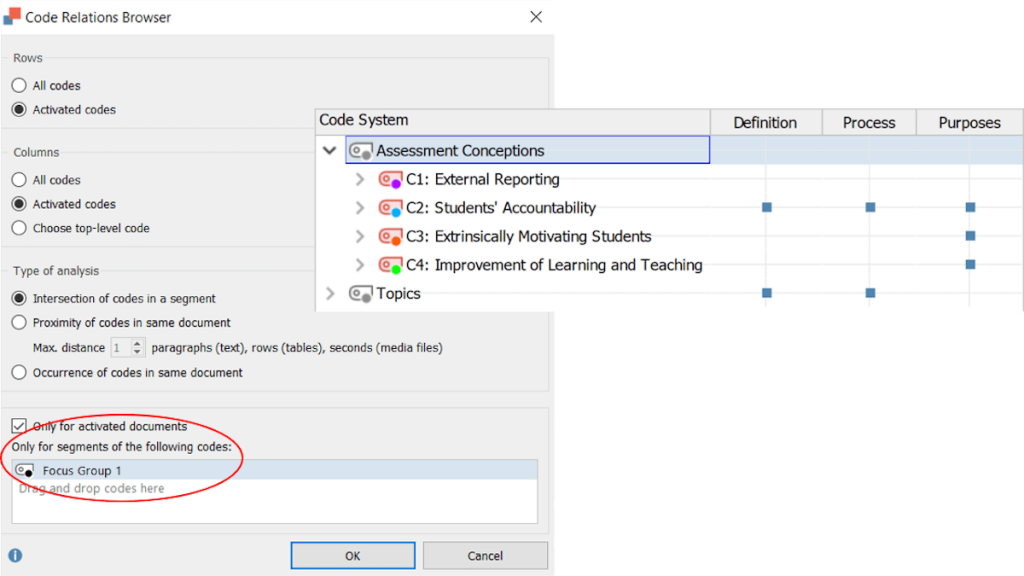

最後に、MAXQDA の[コード間関係ブラウザ]を利用して、インタビュー/フォーカスグループディスカッションの中で最も一貫して存在感のあるカテゴリを可視化しました。

1 人の教師が複数のフォーカスグループに参加しているため、各フォーカスグループを個別に観察することで、結果の整合性を確認しました。コード間関係ブラウザの[以下のコードのセグメントのみ]という機能を利用し、図 6 に示すように、1 つのフォーカスグループのセグメントに限定した出力を確認しています。フォーカスグループの50%以上の人が言及していた場合には、そのカテゴリがクラスの生徒にとって支配的なものであるとみなした。

結果と結論

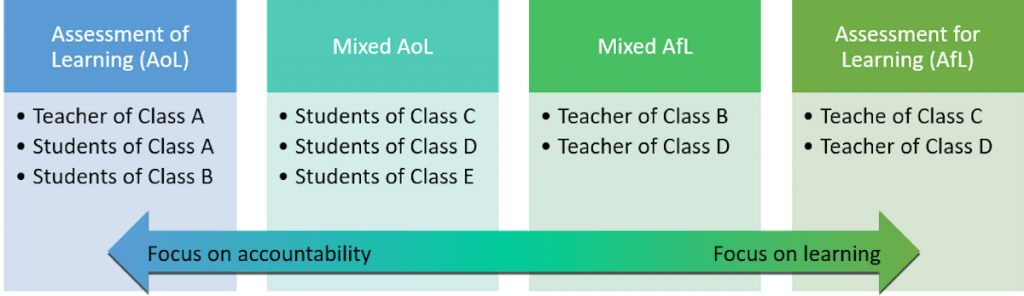

MAXQDA の視覚化ツールにより、4 つの異なる包括的な評価の概念を見出し、学習軸の評価を<AoL(Assessment of Learning) – 証明と説明責任を重視>から<AfL(Assessment for Learning) – 学習と教育の改善を重視>までの連続体に沿って並べることができました(図 7)。

この結果は、生徒と教師の間で評価に関する支配的な概念(生徒はAoL極より、教師はAfL極より)が異なることを示しています。この不一致は、教師が持つ概念と、教師が実践する評価方法の間に矛盾があるためではないかと考えています。

本研究は、FCT-科学技術財団-研究プロジェクトPTDC/MHC-CED/1680/2014およびUID/CED/04853/2016の支援を受けています。

- この投稿は掲載元と著者の許可を得て、MAXQDA Research Blogより日本語訳したものです。

- カテゴリー名の日本語訳など、出力の内容から補足を加えている場合があります。また、原文で「mathematics」となっている部分を、研究対象が小学校であることを考え「算数」としております。

- 詳細は原文Using MAXQDA to Understand Perspectives on Mathematics Assessment – Education Research Exampleを確認いただくことをお勧めします。

References

Barnes, N., Fives, H., & Dacey, C. M. (2017). U.S. teachers’ conceptions of the purposes of assessment. Teaching and Teacher Education, 65, 107–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.02.017

Brown, G. T. L. (2008). Conceptions of assessment: Understanding what assessment means to teachers and students. New York, NY: Nova Science Publishers.

Brown, G. T. L., & Harris, L. (2012). Student conceptions of assessment by level of schooling: Further evidence for ecological rationality in belief systems. Australian Journal of Educational and Developmental Psychology, 12, 46–59.

Brown, G. T. L., & Hirschfeld, G. H. F. (2007). Students’ conceptions of assessment and mathematics: Self-regulation raises achievement. Australian Journal of Educational Developmental Psychology, 7, 63–74.

Brown, G. T. L., Kennedy, K. J., Fok, P. K., Chan, J. K. S., & Yu, W. M. (2009). Assessment for student improvement: Understanding Hong Kong teachers’ conceptions and practices of assessment. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 16(3), 347–363. https://doi.org/10.1080/09695940903319737

Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Opre, D. (2015). Teachers’ conceptions of assessment. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 209, 229–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.11.222

Vandeyar, S., & Killen, R. (2007). Educators’ conceptions and practice of classroom assessment in post-apartheid South Africa. South African Journal of Education, 27(1), 101–115.

About the Authors

Natalie Nóbrega Santos is a PhD student at the ISPA – Instituto Universitário. She graduated with a degree in Educational Psychology from the University of Madeira. Her research interest fields are academic assessment, the affective components of achievement, grade retention, and social and emotional learning. Her present research project is titled “Second-grade retention: Academic, cognitive, and socio-affective aspects involved in decision making.”

Natalie Nóbrega Santos is a PhD student at the ISPA – Instituto Universitário. She graduated with a degree in Educational Psychology from the University of Madeira. Her research interest fields are academic assessment, the affective components of achievement, grade retention, and social and emotional learning. Her present research project is titled “Second-grade retention: Academic, cognitive, and socio-affective aspects involved in decision making.”

Vera Monteiro did her degree and master’s degree in Educational Psychology at the ISPA – Instituto Universitário and her PhD in the same domain at the University of Lisbon. She has been a professor at ISPA-Instituto Universitário since 1991. Her research interests are Assessment and Feedback and their relation to learning. She investigates how assessment and feedback processes can optimize learning. These may be through affective processes, such as motivation, engagement, self-perception competence or/and through several different cognitive processes. That is why she is also interested in students motivation to learn, particularly in the domain of self-determination theory.

Vera Monteiro did her degree and master’s degree in Educational Psychology at the ISPA – Instituto Universitário and her PhD in the same domain at the University of Lisbon. She has been a professor at ISPA-Instituto Universitário since 1991. Her research interests are Assessment and Feedback and their relation to learning. She investigates how assessment and feedback processes can optimize learning. These may be through affective processes, such as motivation, engagement, self-perception competence or/and through several different cognitive processes. That is why she is also interested in students motivation to learn, particularly in the domain of self-determination theory.

Lourdes Mata is an Assistant Professor at the ISPA – Instituto Universitário. She graduated in Educational Psychology and has a PhD in Children’s Studies by the Universidade do Minho. She studies the affective components of the learning processes, aiming to: identify and characterize individual beliefs and affective learning facets among students throughout schooling; and to analyze the quality of education and care contexts taking into account the organizational aspects and teachers’ and classrooms’ related variables.

Lourdes Mata is an Assistant Professor at the ISPA – Instituto Universitário. She graduated in Educational Psychology and has a PhD in Children’s Studies by the Universidade do Minho. She studies the affective components of the learning processes, aiming to: identify and characterize individual beliefs and affective learning facets among students throughout schooling; and to analyze the quality of education and care contexts taking into account the organizational aspects and teachers’ and classrooms’ related variables.